Breadcrumb Trail Links

Opinion Columnists

Article content

If you are reading this, you are doing something remarkable, scary and controversial.

Advertisement 2

Article content

You are also doing something defiant. An illiberal society would have you read only those words and thoughts deemed “acceptable.” That you do not have to pay any attention to this is, in itself, remarkable.

Article content

Welcome to summer and the last week of school. Welcome to beach and poolside reads, books you can take on a road trip, books you can fall asleep to and all the other joys of the season, when nothing is read as homework.

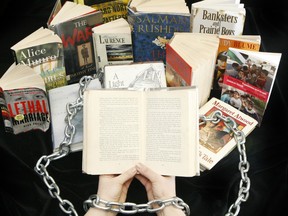

As we welcome the freedom of lazy days, we are living through another brutal phase of prohibition, when affronted adults are determined to keep their children — and other people’s children — away from certain thoughts and ideas.

In their ideal world, children would be taught stories and myths that have been vetted by whatever belief is prominent in their house. Nothing has to be true or real or even plausible. All such stories have to be is acceptable and able to be drummed into the evolving brains of susceptible children. That is in itself unacceptable, but families have the right to determine what they allow in their house. The problem arises when such parents decide other people’s children need to be protected.

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

I was a fortunate child: My parents were readers and so were their children. Nobody censored what was around the house. I remember reading Kathleen Winsor’s Forever Amber, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and the then-equally scandalous Peyton Place by Grace Metalious before being old enough to truly understand the subtext of those books. But I suspect my parents did not much care as long as I was a reader. So I was exposed to everything from my paternal grandparents’ staunch Methodist catechism to my mother’s equally staunch Roman Catholicism and the Baltimore Catechism, thus growing up with a healthy dose of skepticism.

There were no “banned” books in our home. There was no censorship. I learned censorship through attending Catholic schools and learning about the Index, compiled by “official” censors “to prevent the contamination of the faith or the corruption of morals through the reading of theologically erroneous or immoral books.” It was discontinued in 1966, I suspect because curious children would want to hunt out and read the “forbidden” list, which included all works by Jean-Paul Sartre and Emile Zola. Singled out as forbidden were Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert, Notre Dame de Paris by Victor Hugo, and The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir. (One of my favourites.)

Advertisement 4

Article content

All of this came to mind in an essay by A.O. Scott in last Sunday’s New York Times about reading — why everyone loves it, but so many want to control it.

He writes: “Everyone loves reading. In principle, anyway. Nobody is against it, right? Surely, amid our many quarrels, we can agree that people should learn to read, should learn to enjoy it and should do a lot of it. But bubbling underneath this bland, upbeat consensus is a simmer of individual anxiety and collective panic. We are in the throes of a reading crisis.

“Across the country, Republican politicians and conservative activists are removing books from classroom and library shelves, ostensibly to protect children from ‘indoctrination’ in supposedly left-wing ideas about race, gender, sexuality and history. These bans have raised widespread alarm among civil libertarians.”

Scott refers to the “censorious piety on social media and college campuses, where books deemed problematic become lightning rods for scolding and suppression. While right and left are hardly equivalent in their stated motivations, they share the assumption that it’s important to protect vulnerable readers from reading the wrong things.”

Advertisement 5

Article content

Among the most-banned books in the United States are a graphic version of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Rupi Kuar’s collection of poems, Milk and Honey.

In case we want to feel smug about Canada, we are not without blemish. The Diviners by Margaret Laurence; The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz by Mordecai Richler; The Wars by Timothy Findley; Such Is My Beloved by Morley Callaghan; and Barometer Rising by Hugh MacLennan have all been singled out for censure.

So here’s a summertime challenge: read these five Canadian books and let me know at the end of August if you’ve been offended by their contents.

Catherine Ford is a regular Herald columnist.

Comments

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion and encourage all readers to share their views on our articles. Comments may take up to an hour for moderation before appearing on the site. We ask you to keep your comments relevant and respectful. We have enabled email notifications—you will now receive an email if you receive a reply to your comment, there is an update to a comment thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information and details on how to adjust your email settings.

Join the Conversation